Adora Mba didn’t always foresee a career in the art world. The daughter of a Nigerian banker and a Ghanaian lawyer, she was urged to follow in her mother’s legal footsteps. Art however, was ever-present in their home. Adora’s father collected pieces around the world, often with her in tow. Little did the family know what was considered a hobby was quickly becoming Adora’s true north.

A third culture kid, Adora spent her formative years between London, Lagos and Accra. After traveling to the states for University she emerged into the workforce ready to try her hand at journalism. She found success as a producer for ARISE News Network in London and willed herself to the helm of a culture segment—but art was still calling. She followed the gravitational pull toward galleries and art institutions in her spare time, noticing a rise in exhibiting contemporary and African artists and her love of interfacing with them. In the programming driver’s seat of her ARISE segment she steered her audience toward their work and points of view, and pushed those conversations beyond an exclusive art circle.

To fill this void of exposure Adora created The Afropolitan Collector, an art advisory platform that acquired and advanced African art and design. When she moved to Accra in 2018, she made plans to address this need on a grander scale. She was determined to help develop the Ghanaian art scene to its full potential. Now, the art advisor, collector, and writer adds gallery owner to her resume. Located in Accra and “committed to nurturing Ghana and the Continent’s contemporary art community,” ADA \ contemporary art gallery is pushing contemporary African artists to the global forefront. ADA has eight artists on the books: Stacey Gillian Abe, Chinaza Agbor, John Madu, Ekene Emeka-Maduka, Godwin Namuyimba, Collins Obijiaku, Eniwaye Oluwaseyi and Zandile Tshabalala.

Last week ADA launched its third consecutive debut solo exhibition with Tshabalala’s “Enter Paradise,” on view until April 18, 2021. Similar to Adora, Zandile’s family did not view art as a profession. She pursued it anyway. In her most recent collection of works, the Soweto native explores Black women and their “everyday” representations of paradise. These pieces; Tshabalala described, required a leaning into her own true north.

We wanted to know more about Adora and Zandile’s origin stories, work styles and the way they see themselves.

Adora Mba by Daniel Cole Ofoe Amegavie

You’ve mentioned that your Dad was an art collector and there was always art in your home growing up. Did he also purchase African or Black art?

Adora: Predominately, yes. We had a lot of pieces from paintings to sculptures from all over Africa, but mostly Nigerian artists. Saying that, there were the odd international art works in our home too, like Matisse.

What was your favorite piece from your childhood home?

Adora: There was this mixed media three-dimensional artwork of the back of a headless naked woman with real coral beads on her waist made out of some sort of clay textile. It was a very feminine, beautiful piece and rather sexy acquisition for a West African! I loved that we had a work of a naked woman in our foyer, it was the very first work one would see upon entering our home. My friends from school were always so shy about it. My mother used to pretend that it was her body which made my friends blush even more!

It was done by a Nigerian artist named Nsikak Essien who had done an exhibition of his works in our home in Lagos back in 1988 (I was 2). It was actually incomplete (hence being headless), but my father loved it so much he bought it on the spot! My father still has it, still in the foyer but now in his Paris home. It has not aged a bit and looks like it was done yesterday. I think it is both our favourite out of his entire collection.

You’ve also mentioned that you wanted to be an artist as a young girl, what kind of art did you create?

Adora: I guess I considered myself a mixed media/abstract artist. I made most of my works out of elements, especially metals. I loved playing and manipulating metal works, printing on them and seeing their rust and corrosion combined with paint. Funnily enough it wasn’t that work that was considered my ‘strongest’ at the time—I sold a watercolour painting of a dead bumblebee to my English teacher’s wife for £200. I made a sale at 16!

If your path had been to be a professional artist, what would be your ideal medium?

Adora: I honestly don’t know…as a collector and viewer I have always loved paintings. Yet, as a young artist it was certainly mixed media. Perhaps I would have ended up as a Black portraiture artist like everyone else.

You’ve spoken about how the contemporary African art market is lacking in infrastructure as a new and niche market and choosing investments can be a gamble. From the investments you’ve made/facilitated in new African artists, which have had the most return?

Adora: My nickname with my clients is “The Oracle.” To be very honest all the artists I have ever backed or strongly supported, especially emerging African artists, are successful now. I don’t need to give names, let’s just say that I have a strong sixth sense on who to invest in early. I’m thankful for the foresight.

Adora Mba by Daniel Cole Ofoe Amegavie

Museum and gallery culture in the US and the UK can be seen as white dominated and traditionally stiff, unwelcoming and non-inclusive. As you are shaping the infrastructure of the art world in Ghana, what are you taking from those markets, and what are you intentionally doing differently?

Adora: The main difference is inclusion—I believe my mission is [to] make everyone regardless of race or social class feel comfortable to enjoy, consume and acquire fine art. A world where anyone can come into a museum or art space and not feel threatened or judged is important. Living in London, even my father had some ‘looks’ when walking into a Mayfair art gallery. (That was, until he was interested in an expensive or unique work, of course.)

Inclusion is the most important theme for all of us who are in the art market, whether it be collectors, curators, gallerists, writers or artists – we just want to be included. We OUGHT to be included, it is our art, history and culture after all.

Name a skill you have (naturally or from experience) that unexpectedly came in handy as you were launching ADA.

Adora: Patience and letting go. I am a person that is so proactive, perhaps a little controlling and a little impatient—I want things done immediately the way I envision them. But that is not the way, not while living and working in Africa, especially Ghana! I have had to learn to be patient, to trust the process, trust the people I work with and know that it all works out in the end. Which it does!

Can you list the things you look for in an artist you want to work with?

Adora: Strong artistic voice/narrative/point of view, technique, a willingness to learn and evolve.

How about things the current ADA artists have in common?

Adora: They are all brand new to the international art market, and ADA is a new gallery. It feels like we are growing and going through the journey together.

Where would you like to expand ADA in the future?

Adora: I intend for us to be WORLDWIDE.

What are some ways you’ve been challenged as a young African woman entrepreneur in the art world?

Adora: I think that the statement is the answer: I am a young, Black African woman working in a predominately white, male world! Even when it comes to Black and African art the current key holders and decision makers are white men.

It has come with its challenges of course, but nothing new that no other woman in my position has been through regardless of industry. I get more disheartened by the lack of confidence and support from ‘us’ ourselves to be honest, but I like surprising those who don’t believe I can contend. I am focused and have been doing this for a long time in spite of my age. Plus, I have a super alliance and support system behind me so GAME ON.

Do you have any advice for other young Black and African women working toward any career path in the art world?

Adora: Doors close and doors open – keep going and stay true to what you want to do. It is so easy to be swayed and manipulated by what others are doing, you must trust your instinct and inner voice. Despite what is said, there is enough space for all of us! So do you girl, you’ll be just fine.

Art Association ~ Adora Mba

A piece of art …that reminds you of your childhood: I consulted for Gallery 1957 in 2018 for 1-54 Contemporary African art fair (NY edition) and we showed a selection of works by Gideon Appah titled “Memoirs Through Pokua’s Window” dedicated to his grandmother who raised him. Every piece of work we showed reminded me of being a child with my grandparents in Nigeria and Ghana. We even transformed the booth to recreate the artist’s grandmother’s home with an old TV, sofa, family albums, old liquors she loved. That was a really emotional show for me, in a good way.

…that makes you imagine the future: Seeing works by current emerging artists that are so unique. Works by Emma Prempeh and Michael Armitage for example. They both make me think of the future of the art market and where it is heading for Black and African artists.

… that calms you when you’re stressed: Oh, this is easy, photography does that. I love Lakin Ogunbanwo’s Hat series “Are We Good Enough”, 2012 – ongoing (WHATIFTHEWORLDGALLERY) or any photography book. Current favourite “Africa State of Mind” by Ekow Eshun.

… you’d love to have in your home: A large-scale Lynette Yiadom-Boakye or Ndidi Emefiele painting.

… you wish you’d created: Modupeola Fadugba’s art. I get a little jealous and yet totally mesmerised by her work ethic, research and paintings at the same time!

“It is so easy to be swayed and manipulated by what others are doing, you must trust your instinct and inner voice.” – Adora Mba

You mostly use acrylic and oil paint in your pieces. Are there other mediums you see yourself working with in the future? Why or why not?

Zandile: In the future, I hope to get into sculpture and textile. With sculpture, I always think about my work being more three dimensional and the audience engaging with it in that manner. Textile is more related to my interest in fashion, again it would be interesting to induce more engagement with my works, in a more functional way and within everyday material.

We’ve seen your process described as sketching on canvas and then painting; letting the rest of the piece come together intuitively. Does working with oil lend itself to that practice, as it stays wet and pliable longer than acrylic?

Zandile: Working with acrylic allows me to make decisions a bit more quickly. Because of its fast-drying nature, I am able to web my thoughts and change my mind if necessary, without having to worry about the wait that much.

There appears to be a recurring character in your paintings. Is this intentional? Who is she?

Zandile: In my work, I do a lot of self-portraits although I am not really interested in having the figures look exactly like me. I sometimes have other sitters in my paintings, but even with them there’s still a lot of me reflected in their character, pose and gestures. So again, it becomes more or less like a self-portrait/reflection. It is very much intentional, I’m a firm believer of having the self as a starting point.

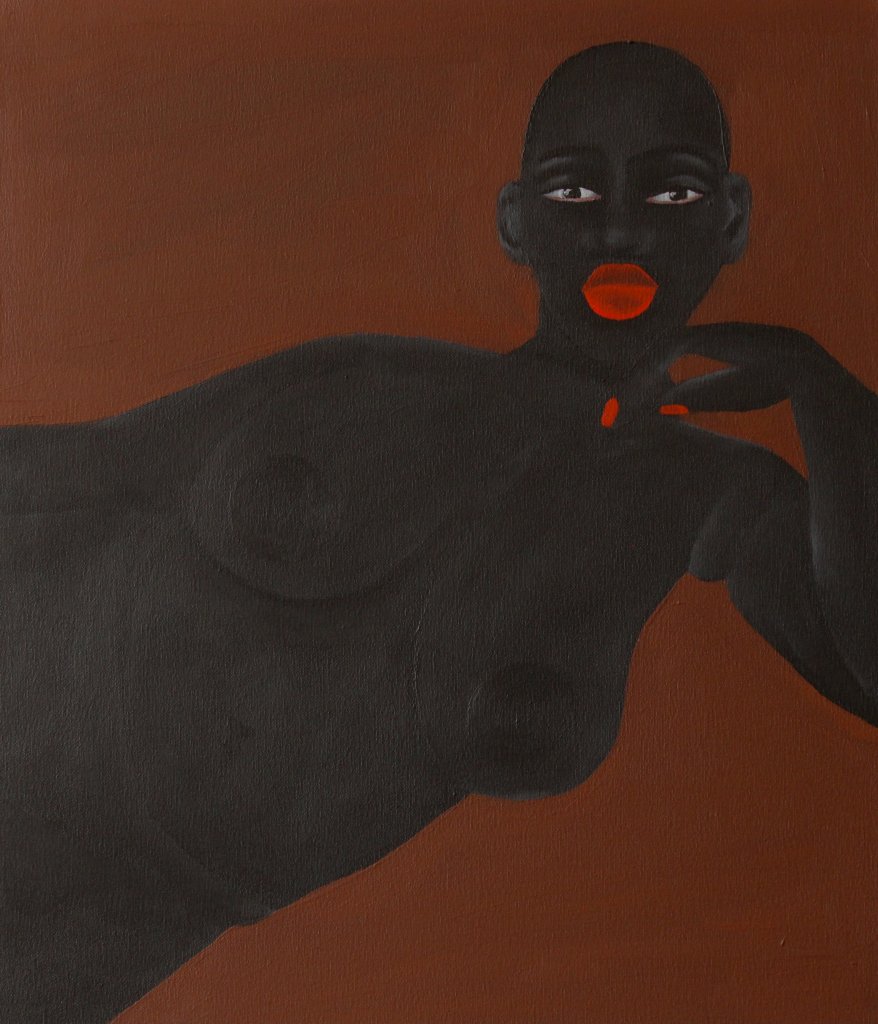

Enter Paradise I — Acrylic on canvas 60 x 70 cm 2020

Enter Paradise II — Acrylic on canvas 60 x 70 cm 2020

You’ve said in previous interviews that you’re very in tune with your imagination and love dreaming. Have paintings ever come to you in a dream? If so, what’s your process for remembering and capturing them on the canvas?

Zandile: Unfortunately, I have not dreamt of paintings or future compositions. They come a lot from memory and observation. I tend to resist my childhood memory very much and often feel like I’m experiencing multiple déjà-vu’s. There’s a feeling that repeatedly comes along with those memories and I use that to connect even further with my work. The process is more like finding/making reference images of the posture and setting that which I had envisioned; that is my foundation…from there onwards I rely on my intuition on what else should be present, the colours I should make use of. Again, it’s memory and feeling that lead me.

You’ve said that the magic often happens in art when you stop overthinking. What are some ways you get out of your head?

Zandile: To begin painting, I think that the overthinking often happens when I am not painting. Once I begin, my focus is on my canvas.

Your piece Glenda depicts your mom and starts the conversation of Black women and busyness. Outside of your art, what are some ways that you normalize rest?

Zandile: Outside of my work I try to practice what I preach by listening to the needs of my body and mind. I am gentler with myself and allow myself to rest as much as I need to. My guilt to always be busy tries to distract me, but I try to fight back. I have days for practicing “the art of doing nothing” which I learnt from the book/movie “Eat, Pray, Love.”

Many of your pieces shatter and reframe stereotypes and misconceptions about Black women and women in general, for example your Mother/Cow series. Are there any misplaced narratives about Black women that you are passionate about and haven’t yet tackled in your art?

Zandile: Currently I am engaging a lot with love in my personal life and what kind of love I have been conditioned to centralise in my life. I think it would be nice to attempt to tackle that on canvas as well. What kind of love have we centralised as Black women, and why.

What was the impetus behind this exhibition?

Zandile: I was working and thinking around the term “paradise,” what it means to me and where it exists. I have engaged with the term differently from how I engaged with it in my previous series titled “Paradise.”

Proud Nude I — Acrylic on canvas 60 x 70 cm 2021

Proud Nude II— Acrylic on canvas 60 x 70 cm 2021

Art Association ~ Zandile Tshabalala

Liken your art style to…a genre of music: I’d say Alternative/indie. The likes of FKA Twigs, Sevdaliza.

… a genre of literature: African novels at most and African academic theorists. “Untitled” by Kgebetli Moele; Audre Lorde’s essay “The uses of erotic.”

… a period of fashion: Haute Couture, I believe it is more of a movement, but I think that it is closely related to my work.

Liken your personal style to…an art period: Renaissance.

... a genre of film: K-drama romance.

… a period of architecture: Gothic architecture.

“I’m a firm believer of having the self as a starting point.” – Zandile Tshabalala

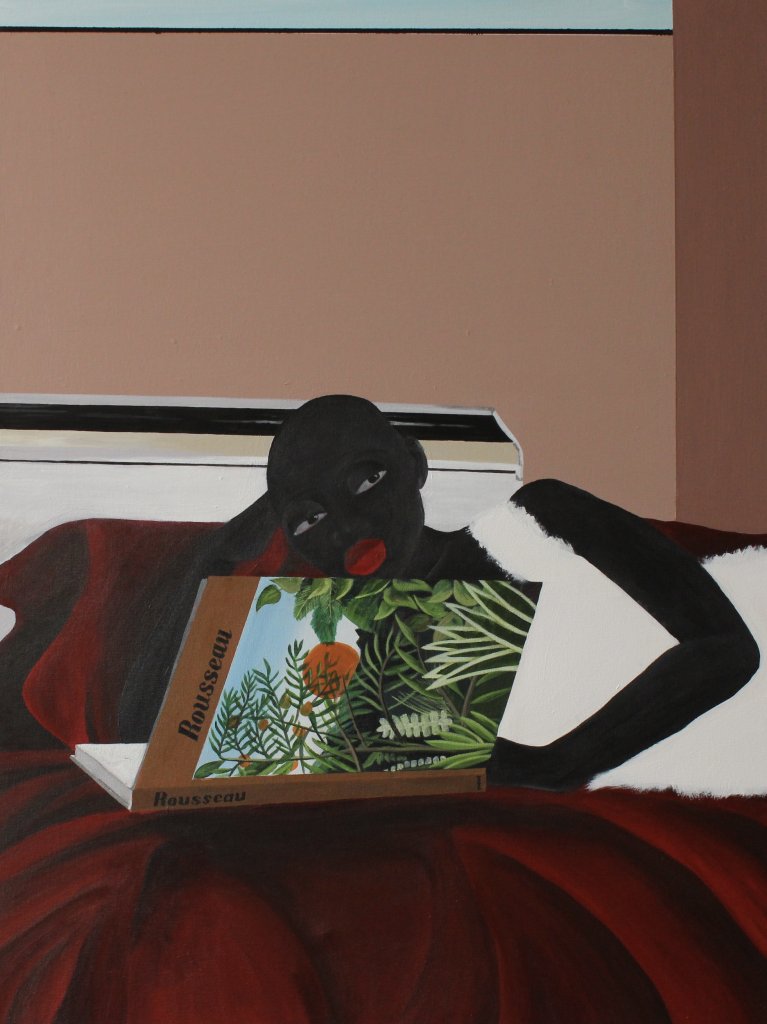

Ode to Rousseau I — Acrylic on canvas 90 x 120 cm 2021

Ode to Rousseau II — Acrylic on canvas 90 x 120 cm 2021